Designing Light & Story for The Prince of Egypt

Designing Light & Story for The Prince of Egypt

It’s been a few months since The Prince of Egypt closed at Hale Centre Theatre, and yet I still find myself thinking about it. Some shows stay with you—not just because of the scale or the challenges, but because of what they taught you as a designer. This one did that for me. I’ve been meaning to write about it for a while, and now feels like the right time to reflect on the process, the collaboration, and the moments that made this production so meaningful.

At Hale Centre Theatre, spectacle isn’t optional—it’s the standard. Our venue is in-the-round, equipped with a fully automated Tate stage system, dual gantries for massive scenic drops, and a lighting rig with over 120 moving lights. Everything moves. Everything flies. And the audience sees it all from every angle.

So when we took on The Prince of Egypt, I knew this production needed a design language that could match the spiritual and emotional scale of the story—something immersive, sculptural, and alive.

Director’s Vision: Scale with Soul

The foundation for the visual language of The Prince of Egypt began with director Dave Tinney’s powerful concept: a show that honored the sacred nature of the story while embracing the scope and theatricality required to tell it in-the-round. Dave’s vision drew from religious texts, interpretive movement, epic cinematic motifs, and a balance of allegory and reverence.

This inspired the entire design team—from scenic to sound to costumes and, in my case, lighting and projection—to work not just in service of spectacle, but in service of story. Every image, shadow, and texture was developed with that goal in mind.

The Rope Ring: Projection in Three Dimensions

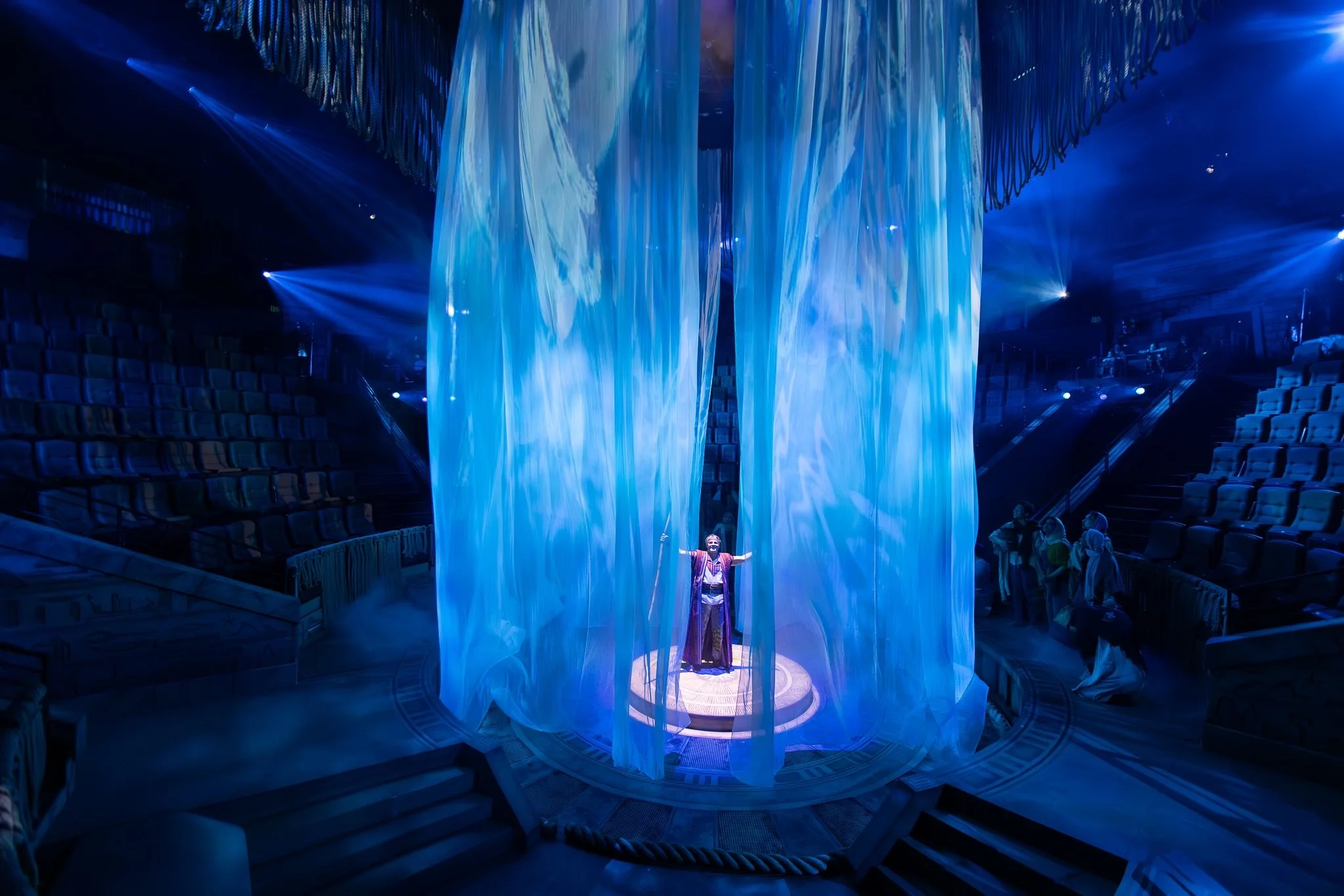

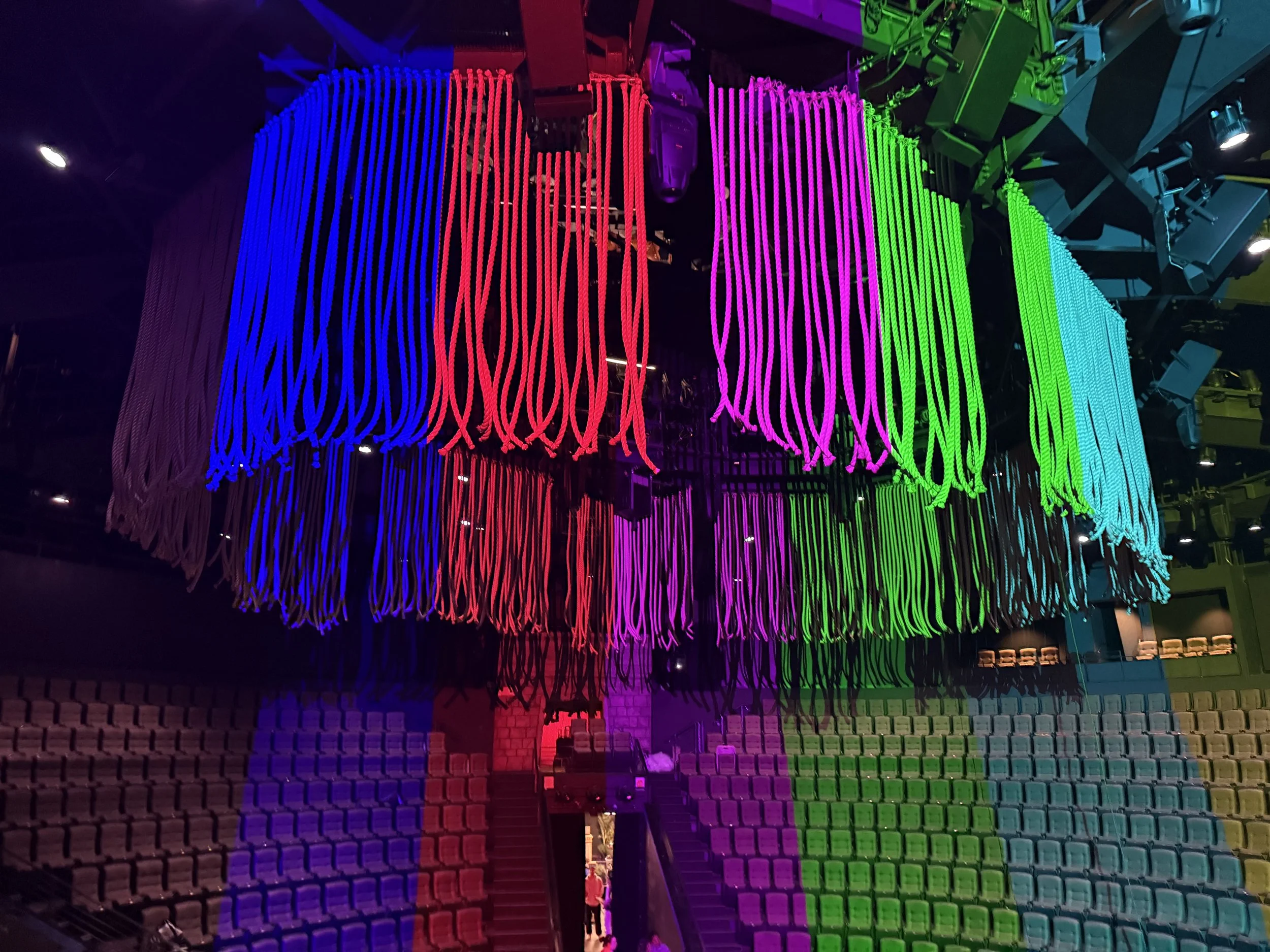

One of the boldest choices we made was suspending a full circular "rope ring" above the stage—hundreds of thick ropes forming a tactile, 360-degree projection surface. Collaborating with scenic designer Nate Bertone and the incredible Hale Centre Theatre design and production teams, we designed the rope ring as both scenic architecture and projection canvas.

It wasn’t just about imagery—it was about transformation. Projecting onto rope meant embracing distortion, depth, and shadow. With four high-powered Christie Griffyn 34K projectors dedicated to the ring (and four more mapped to the stage floor and scenic surrounds), we built a constantly shifting visual world that shimmered, fractured, and breathed with the action.

Some moments—like the burning bush or the plagues—used the rope to obscure, revealing images in slivers. Others used it as a wash, casting sunsets, sandstorms, and palatial murals around the audience in all directions.

Lighting and Projection: One Design

As both the lighting and projection designer, I approached the entire visual structure as one integrated system. Under Dave Tinney’s direction, the storytelling was never just about what looked good—it was about emotional weight, spiritual symbolism, and theatricality in its purest form. Dave’s concept asked for a design that felt ancient, sacred, and immersive without ever becoming overly literal.

A perfect example is what we called "The Secret Room." The elaborate floor design seen in production photos isn’t painted—it’s projection, precisely mapped to hold depth and structure under all angles. The rich blues? Pure lighting. And the key source of warmth? Practical fire, accented with moving light shimmer to elevate it beyond realism. It was all one design: multiple tools working together to build an environment that answered Dave’s vision for cinematic theatricality grounded in faith.

Throughout the show, projection established scope and setting—temples rising across the rope ring, sand swirling beneath characters’ feet—while lighting carved out emotion, rhythm, and tone. Sometimes the content took the lead. Other times, the light told the audience where to look and what to feel. But in every case, they worked together to serve the story.

Color and Saturation: Visual Storytelling at the Core

For The Prince of Egypt, color was dramaturgy.

Each environment had a defined palette strategy, drawn from extensive research and fine-tuned with saturation curves and color temperature blending:

Sun-baked ochres and terracottas for daylight in Egypt

Rusts and deep shadows for the slave city and construction sites

Lush greens and sky blues for Moses’ time in the valley

Deep indigo, gold, and crimson for divine or supernatural sequences

Desaturation often marked moments of tension or spiritual absence. Bursts of saturated color signaled revelation, deliverance, or wrath.

Because I controlled both projection and lighting, I could shape how those color moments landed. A cue wasn’t just about what was projected—it was about what light supported it, broke it, or extended it.

Design Process: Building a Visual Language

Before a single cue was programmed, Nate and I built a comprehensive visual language using a shared design board in Freeform. It featured:

Architectural research for each space

Thematic color swatches for each act or setting

Gobo texture studies and shadow reference

Period artwork, environmental concept art, and cultural inspiration

The board kept us visually aligned from previs to final tech. Every choice was rooted in story.

Previsualization: Designing in the Dark

My associate, Collin Schmerier, and I built full previs environments to test lighting and projection cues before we ever entered the space. Scenes like the construction site were pre-programmed down to angle, timing, and texture. Because of that prep, we walked into tech already knowing what the lighting was going to do in that sequence—which meant we could shift our focus to the more complex elements, like the performer flying moments. Rather than troubleshooting cues on the spot, we were able to fine-tune integration with automation and staging. That efficiency gave us the flexibility to get more out of every tech session and let the artistic side lead.

This level of integration wouldn’t have been possible without the tight collaboration of my associate Collin Schmerierand projection programmer Keaton Mangelson. The shot below was taken during our first full-scale rope ring test—mapping content across all four overhead projectors while balancing color, blend, and alignment in real time. It was one of those moments where months of planning met the rig… and actually worked.

It also helped us plan for parallax, shadow spill, and interactions with the automation lifts—all major factors in a venue with this level of complexity.

The Technical Backbone: 8 Projectors and Disguise Servers

The show ran on a projection system powered by eight Christie Griffyn 34K projectors:

Four mapped to the rope ring

Four mapped to the stage and surrounding deck

All were driven by Disguise gx 2c media servers, giving us flexible control, fast renders, and precise cue syncing. This infrastructure was essential not just for scale, but for nuance. We were projecting on curved, moving, textured surfaces—anything less powerful wouldn’t have held up.

Beyond the rope and the deck, we wrapped the upper ring of the theater with scenic carvings that doubled as subtle projection surfaces. These 360° screens gave us even more room to extend the visual world—echoing motifs, introducing movement, and surrounding the audience with light and content. When these surfaces lit up, it felt like Egypt was breathing over your shoulder.

Critical Response

In a glowing review, BroadwayWorld praised the production's design as "a wonder to behold," calling the scenic environment "truly stunning" and highlighting the seamless integration of projections and lighting. The review specifically noted how the encased projection surfaces and immersive design created a world that was "transportative and thrilling." The collaboration between scenic designer Nate Bertone and lighting/projection designer Jaron Kent Hermansen was spotlighted as a key force in building the ancient and mystical world of The Prince of Egypt.

Final Thoughts

The Prince of Egypt wasn’t just a spectacle—it was an exercise in integration. Every element had to speak to the story, to the scale, and to the sacred.

Being able to work with both lighting and projection allowed for a unified design voice—one that could sculpt mood and myth at the same time. And doing it all in-the-round, at Hale Centre Theatre, with this team? That’s why I do what I do.

Photos by: Jaron Kent Hermansen, Leavitt Wells, Nate Bartone, Tyson Leavitt

Disclaimer: The views and reflections shared in this post are my own and are based on my personal creative process. While I’m proud to be an employee of Hale Centre Theatre and a member of the incredible collaborative team behind this production, these thoughts do not represent the official views of the organization. I believe deeply in the power of collaboration, and I gratefully acknowledge the many artists, technicians, and storytellers whose work brought this show to life.

Click below to view the digital program for this production